Saturday 18 February 2017

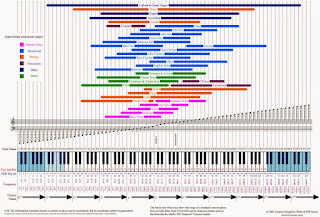

The Ultimate EQ Cheat Sheet for Every Common Instrument

Sometimes a guitar cab gets mic'd up differently night to night, plus every voice is unique, and every snare drum "speaks" differently (just ask a drummer). All of these minute changes and differences can and will affect the EQ decisions you'll have to make. This is why I'm such a strong believer in ear training and learning how certain parts of the frequency spectrum present themselves outside of their source-specific applications. That being said, these tips can be helpful as a place to start your search, but are not gospel by any means. So without further adieu, let's begin.

A subtractive approach to EQ

Not everyone's ethos on EQ is the same, and most people may never see eye to eye on EQ approach. That being said, I come from the camp that subtractive over additive tends to be better for your mix in most cases. Now, I'm not saying to live in a strictly subtractive world; I do make boosts from time to time when needed or appropriate, but it's probably a 3:1 or 4:1 ratio of cuts to boosts.Also, a quick note on the topic of high pass filters: use them. They can be your best friend, but be careful as they're a double-edged sword. HP filters can quickly clean mud from your mix and open things up, but too much can lead to a thin, weak-sounding mix equally as quick. When applying them, I like to come from the top down, as I find that easier to dial in properly. By that, I mean instead of rolling up an HP filter and listening until I think it's removed what I'm looking for, I start way above with "too much" HP filtering and roll it down until I feel that I have all the information on the bottom I need. I find it easier to hear the effect this way, which therefore allows me to more accurately and effectively control my low end.

Here's a detailed, instrument-by-instrument guide to EQ.

Drums

Kick

While the snare may arguably be the most vocal drum in the kit, the kick has an amazing array of possibilities for tonal shaping. In many ways, I think you can really measure an engineer/mixer's abilities on how a kick sounds and how it sits in the mix.

- 40 to 60 Hz - Bottom: The tone of the reverberation in the shell, sometimes too rumbly, can be undefined/indeterminate depending on the mic'ing/speakers

- 60 to 100 Hz - Thump: The "punch you in the chest" range of the kick

- 100 to 200 Hz - Body: This is the "meat," if you will, of the kick sound

- 200 to 2,000 Hz - Ring/Hollowness: This large band is where you can often find issues with ringing and muddy kick sounds.

- 2,000 to 4,000 Hz - Beater Attack: This is the range to look for the "thwack" sound of the beater, critical for getting that "basketball bouncing" kick sound.

Snare

- 200 to 400 Hz - Body/Bottom: The central fundamental of most snares tends to live somewhere in this range

- 400 to 800 Hz - Ring: This is the range that tends to give that hollow "ring" to a snare tone that's often undesirable. Crush this range too much, though, and your snare will start to lose some life and sound two-dimensional in the mix

- 2,000 to 4,000 Hz - Attack: The stick on head "crack" is often found around 8,000 Hz (Sizzle and Snap). The overtone sound of the snares themselves can either be accented or dampened somewhere around this point.

Toms

- 100 to 300 Hz - Body: Depends on tuning, but a good place to look for the "boom" of a tom sound. Too much and things will sound, well, "boomy." Remove too much, and your toms will sound like cardboard boxes

- 3,000 to 4,000 Hz - Attack: Just as it sounds, this is the the attack of the drum itself from a stick on its head

Cymbals

- 200 to 300 Hz - Clank: Here's where, especially on your hi-hats, the "chink" sound of the cymbal lives. As always, season to taste

- 6,000 Hz and up - Sizzle: This range is where the "tssssssss" part of the cymbals can be brightened up to add some more life and "air" to a cymbal wash, or you can spontaneously start bleeding from the ears if used without prejudice

Synth "Kick" (808)

Ah yes, the 808. It's often used and referred to as a kick, but it tends to act more as a very low tom, as it has a pitch. This thing is the Loch Ness Monster – there tends to be more under the water. The best way to deal with a true, clean 808 sample is to work around it. It's usually best to let the 808 do its thing and to get the bottom end around it the hell out of the way. If it's a fuzzy sample or has been driven and squashed, you may need to play with things above 250 Hz, but usually live and let live is the best approach.

Bass

The reason the kick and the bass tend to be mortal enemies in many mixes is they can literally occupy identical sonic space from a frequency perspective. So before reaching in with any EQ, listen to both and decide where one will take the lead over the other, and in which ranges.

- 40 to 80 Hz - Bottom: Especially with five-string variations, this is where the bottom resonances of most basses live

- 80 to 200 Hz - Fundamentals: The primary fundamental of the bass. Right around 180 to 200 Hz is where you can try to cut in on a bass that is too "boomy" to clean it up while preserving fundamentals.

- 200 to 600 Hz - Overtones: These are the upper harmonics of most bass tones, depending on the sound you're interested in. If you're having trouble getting a bass to cut through in a mix, especially a low-end heavy one or one that's getting played back on smaller speakers, this can be where to look.

- 300 to 500 Hz - Wood: Particularly in upright basses, it's that distinctive, woody bark

- 800 to 1,600k Hz - Bite: The growl and attack of most basses can be either emphasized or toned down around here

- 2,000 to 5,000 Hz - String noise: Pretty straightforward here, I think.

Guitar

Acoustic

- 120 to 200 Hz - Boom/Body: This is where you'll find most of the explosive low end on a mic'd acoustic that tends to feedback in the live world or be disruptive in the studio. A little bit here adds warmth and fullness on a solo performance, but in a dense band mix, it's probably better to get it out of the way

- 200 to 400 Hz - Thickness/Wood: This is the main "body" of most acoustic tones. Too many cuts here, and you're going to lose the life of the guitar somewhat

- 2,000 Hz - Definition/Harshness: This double-edged sword band will give the definition to the acoustic tone to hear intricacies in chords and picking, but too much will make it harsh and aggressive

- 7,000 Hz - Air/Sparkle: A touch, and I mean a touch, of a shelf boost here can help open up an acoustic sound

A note on acoustic guitar pickups (piezo, in particular): Making crazy 10 dB cuts? Contemplating making some absurd boost? You're probably not wrong – the acoustic pickup world can be the Wild West when it comes to tone. Some are great, and some are downright questionable. There are too many variables to even begin suggesting frequencies, so use your ears to guide you home on this one.

Electric

In general, I find a light hand with broad strokes to be most effective on electric guitar, if any EQ is applied at all other than some filtering. If you do decide to go hunting, however:

- 80 to 90 Hz and below - Mud: Lose it, crush it with your HP filter. There's pretty much nothing useful down here, and it will almost always just equate to flabbiness and noise in your tone

- 150 to 200 Hz - Thickness: This is where the "guts" of a guitar normally come from, but again, can quickly cloud a mix on you. Use sparingly, perhaps automate to add sweetness to a solo section or an exposed part, and then tuck it away when things thicken up again

- 300 to 1,000 Hz - Life: I call this the "life" of the electric, as many of the things that make an electric sound like an electric live in this range. So attenuating needs to be taken into consideration carefully. Too much though, and you start fighting with your snare and things like that, so take note

- 1,000 to 2,000 Hz - Honk: This is where honky and harsh characteristics can usually be smoothed out with a wide cut centered somewhere in this range

- 3,000 to 8,000 Hz - Brilliance and Presence: This is the range that can add shimmer or allow a guitar to cut through a mix when boosted. It can also be where you make cuts to keep a guitar from conflicting with a vocal. If making boosts in this range, keep an eye (ear?) out for noise, as any noise present from distortion/effects pedals will very quickly be accentuated as well

Keyboards

Piano

When looking at acoustic pianos, there are so many variations that can lead to differences in tone: upright vs. grand, hammer types, mechanical condition, the player, mic choices, and mic techniques. No matter what, though, the piano tends to be a behemoth in the mix – for better or worse – so most often you'll be looking to cut holes out for other things in your mix.

- 100 to 200 Hz - Boom: This can be a great place to add a little warmth to a solo piano in a studio environment, but more often than not will be the first place to cut some of the girth in a piano in a mix or help reduce feedback potential in a live situation

- 3,000 Hz and above - Presence: Adding a little "air" here can be great to brighten up a dark piano tone, depending on mic placement. Be careful not to bring out the noise of dampers on strings (particularly in the 3,000 to 5,000 Hz range), as this can quickly become distracting and jarring

Electric Piano (Rhodes)

If we're dealing with a real electric piano over a sample, things can be very situational as amp, mic'ing, and condition of the instrument itself can play such a huge role.

- 100 to 200 Hz - Boom: As with its acoustic counterpart, the low end can go from lush to overgrown Jurassic underbrush quickly. Particularly with the rich, dense harmonics of something like a Rhodes, cutting "mud" is usually your first order of business

- 800 to 1,000 Hz - Bark: Managing the "bark" and damper noise can sometimes be an issue, but if things are cutting through too much, odds are it's somewhere in this range

Clavinet

Honestly, I find myself treating this similarly to electric guitar, which is fitting considering the method of sound production. There are some idiosyncrasies to navigate with the attack that set it apart from its shoulder-slung brethren, but many of the same principles apply.

Much of a B3's magic comes from good mic placement and the player (the right drawbar settings are game changers). EQ should be applied sparingly and mainly as a corrective measure. Usually it's good to look to anything clashing with the bass (80 to 180 Hz), and if it's feeling a little "chubby" in the middle and either can't get out of its own way or doesn't play nice with other mid-heavy instruments or guitars, look to make cuts somewhere between 300 to 500 Hz.

Synths

While the near-infinite possibilities in the synth world can make this a hard one to generalize, there are some places you may start to look:

- 400 to 600 Hz - Thickness: Many synth sounds can get kind of muddy in this range and mess with the clarity of the sound itself, especially when you start layering multiple synths. Searching somewhere in this range is a good place to start

- 1,000 to 2,000 Hz - Cut/Bite: This is where you can usually find the attributes of a synth patch that are going to help it poke through the mix. Cut here to help tuck something back and out of the way, from guitars to vocals

- 3,000 to 4,000 Hz - Presence/Clarity: Also like voice and guitar, this range helps add excitement to a sound. And also like just about everything else mentioned here, too much of a good thing can be painful

Horns

Saxes

- 300 to 400 Hz - Honk/Woof: This somewhat depends on what type of sax we're dealing with, soprano to baritone. As we go lower, this point is also going to move lower

- 1,000 to 2,000 Hz - Squawk: Again, the type of sax itself may cause this point to float a little more, but you can cut the "parrot on a 'roid-rage bender" tendency of some instruments here

- 6,000 Hz - Reed noise: As saxes generate sound from a thin piece of wood vibrating in an air stream, there's a noise that sometimes accompanies this. Right around this point is where to start looking for that vibration

Brass

This can be applied to all brass in general, but particularly with trumpet and trombone in mind.

- 100 to 200 Hz - Boom/Mud: This is particularly pointing at the trombone, as it sometimes shares the range of the bass and the rest of the rhythm section, but rarely functions in that purpose. Getting it out of the way is usually best, as this range will serve little except to cloud most mixes

- 4,000 to 10,000 Hz - Brightness: This top end can brighten up a dark horn section. However, trumpets can nearly take someone's head off in this range with a good blat, so managing this band is key here

Vocals

The human voice: simultaneously one of the most fickle and yet most important pieces of any mix. Male voices, though typically lower than female, are actually more complex in their overtone structure, meaning that at least equal attention needs to be paid to the high end of a male vocal as a female.

- 100 Hz and below - Rumble: For most vocals, all you'll find down here is mic-handling noise, stage/floor vibrations, air conditioners, etc. Get rid of it

- 200 Hz - Boom: This frequency is usually where you'll find the "head cold" sound. The female voice may run a little higher, but this is the ballpark. Anyone with allergies or sinus issues knows exactly what I'm talking about

- 800 to 1,000 Hz - Word Clarity/Nasality: Not enough and intelligibility of some lyrics may be unintelligible, too much and you get the teacher from Peanuts

- 3,000 Hz- Presence/Excitement: This is right around the point that tends to add some energy, or some "buzz" to a vocal. Not enough, and the vocal may sound deflated, flat, and dull. Too much, and your listener will feel like he or she is getting poked in the ear canal with a chopstick every time the vocalist opens his or her mouth

- 4,000 to 8,000 Hz - Sizzle/Sibilants: Typically this is the range a de-esser is handling. If your vocalist sounds like meat hitting a hot pan at the end of any word ending in "s" or a similar sound, this is where to hunt

- 10,000 Hz and up - Air: Want to "open up" your vocal a little? Apply a light shelf boost around here and that should do it. This is not always necessary, though, and simply adding "air" for the sake of it can make things harsh, brittle, and introduce noise to the sound

Credit :- blog.sonicbids.com

Thursday 16 February 2017

10 DJ Tactics For When People Won't Dance

|

| For good DJs, an empty dancefloor is not a problem, it's an enjoyable challenge of DJing. |

Any experienced DJ, no matter how good or professional, has encountered dancefloors that just refuse to react as expected.

Sometimes, you're confronted with a crowd that it seems just won't dance, no matter how hard you try. It can be confusing to you how one night girls can be dancing on top of the bar gyrating to your tunes and giving you flirty smiles when the next week you seem to have weird, serious looking people and zero energy on the dancefloor, no matter what music you play.

It's not your fault!

First, understand that there are a number of different circumstances that can change the mood and feeling of your night unexpectedly. You as a DJ have to be ready for them and know how to react to this when it happens.

Events taking place in the town or city that you're playing at, door policy and even the weather can influence the crowd that turn up to your nights.

Just as a sudden surge in warm weather and sunshine makes people feel happy, energetic and horny, a blast of rain can do the opposite and take the mojo out of your night.

Big events in town related to fashion, sports or business may all mean you have to adapt to the crowd and go outside of your comfort zone to make people dance.

An overly zealous door policy can see the real party animals getting refused entry and your dancefloor filling up with people who don't seem to care about your music.

All this can be a challenge for your usually lively dancefloor! So what can you do about it as a DJ? Well, the first thing is to relax. There are a number of ways of dealing with the floor that won't dance, so there's no need to panic: as a DJ, you can try all of them. Here they are:

1. Have your secret weapon tunes ready

Create a list of tracks you can play as secret weapons. You should make a rule to only ever drop these when you have a really limp crowd or people who only dance to cheese. Make sure that around half of these are well-known favourites and the other half discreet dancefloor bombs that you've found yourself.

Don't ignore top 40 hits or old party hits because you don't like them. You may hate Cyndi Lauper's Girls Just Wanna Have Fun or Katy Perry's latest chart hit but these tunes could spark life into a lame night for you.

If you really find it painful to play music that's considered cheesy, then find or make remixes of well-known hits to play instead. Justice's remix of the Britney Spears song Me Against The Music is a great example of where cool electro meets top forty hit. That way you can be cool and play to the top 40 crowd at the same time!

2. Find and know more music genres

To be able to react to different people you should be getting into different genres. Mastering one genre is fine but don't be a one trick pony. You really need to be a pro at knowing other genres too in case your crowd don't react quite as you like.

Organise your tunes so that you can flip to a different genre or sub-genre if your crowd aren't digging the music that you're blasting out.

Get to know and enjoy tunes of at least two or three other genres you are familiar with, identify the tracks people will dance to and try them out. You'll see this come in useful time and time again to wake up the energy on the floor.

3. Find tunes that you know girls dance to

When it comes to the dancefloor it's all about the girls. Why is this? Because when girls dance, not only do they look good but you'll see an army of boys follow them straight onto the floor to try to bust out a few hot moves.

These boys don't always care what music is playing, they'll just head to the floor when they see a hot girl dancing to try to cut some shapes and impress her.

Use your experience to make a list of proven girlie tunes, then release them when you feel the dancefloor needs a boost. You'll see those ladies liven up the dancefloor pretty quickly. Then watch the boys follow them blindly onto the floor, and chuckle to yourself.

4. Relax and become one of the crowd

|

| Get out of your DJ box and mingle with the crowd. your enthusiasm and friendliness can be a vital ingredient in getting people relaxed and then dancing. |

All too often, we take ourselves a bit seriously as DJs. After all, aren't we there to play some cool trainspotter tunes that no one else has discovered? Don't you want to show that you know the best cool music around that no other DJ can get? You know, showcase some real hardcore DJ tunes with effects. Yeah!

Well... yes and no. You can educate people and take them on an adventure of musical discovery. But what people really care about isn't you in your booth. It's them and their night out. That's right. All they want to do is enjoy themselves and have a good time.

Learn to relax when playing out and don't take yourself seriously. Enjoy playing out. Have a drink if it helps you get onto the same wavelength as the people there. Chat to some people near you, head out of your booth and mingle a bit. You'll feel better and less tense to be part of the crowd.

Very often, as soon as you relax you'll find yourself automatically playing tunes that people dance to instead of ones that you thought you "should" play.

5. Think positively

Without trying to sound like a sales guru trainer, you have to be able to react positively as a DJ.

Being very positive really does help you when DJing as you'll need to constantly boost yourself if the night isn't going as well as planned. Moaning that your crowd are a bunch of losers when they don't react to what you play won't help you at all and it certainly won't make them dance!

If they're looking like they just came from a funeral when you drop your peak time hits just smile, be cool and tell yourself you're going to turn it around. My DJ sets became better when I started to think this way.

You need to develop a reflex reaction to negative situations on the floor. Tell yourself that everything is going to go well and you'll find the music that makes them dance no matter what's happening.

6. Look at your dancefloor

Looking at who is out to have a good time tonight helps you gauge the atmosphere and get a feel for the kind of music they may like. Are your crowd more black, white, Asian or Latin?

Without generalising about their music tastes, the way people look can help you get an idea of what will make them dance. Are there more boys or girls? Straight or gay? Drunk or high?

Using your common sense to make decisions about what tunes to play, try them out and keep looking up at them from time to time to get a feel for how it's going.

7. Take a request

|

| You may not like to take requests, but they can be just the thing if you need to get the dancefloor going in a hurry. |

We all know DJs who refuse to take any requests but you should think about being open to listening to what people say if no one seems to be enjoying themselves. If you have a group of seven pretty girls who promise to dance if you play Basement Jaxx, then why not play it?

You can be sure it'll get some others on the floor too once a group starts to dance. Their request might be what you need to open up a bit and get the musical juices flowing.

8. Play out as often as possible

As a general rule, playing anywhere from the local hairdresser to the coolest club in town to the old people's home around the corner will help to expand your musical knowledge and develop your DJ intuition. So go ahead, programme your friend's party playlist, play out anywhere and observe how people react in certain situations.

You'll learn much more about how music makes people react according to their mood, persona and the time of night or day.

9. Invite your friends along

If you're not already doing this, then you should be. Make sure you do more than create a simple event on Facebook. Many people receive several Facebook event invitations per day and pay little attention to them. Be better than this and send only personal notes to more influential, musically minded friends of yours and those who know a few people who like a night out. People react far better to a personal message.

Invite plenty of girls that you know who are likely to enjoy the night. Rotate your groups of friends to keep them fresh so you invite new ones each time you play.

In smaller venues, having your loyal group of dancing friends present can save your life for getting people on the floor.

10. Start dancing yourself

If the crowd really do seem to be a lame bunch and refuse to move any parts of their body no matter what dancefloor bombs you drop, then start dancing away yourself in your booth. After all, you've done all you can, so you may as well just enjoy yourself!

Grab a drink, put on some great tunes and dance away to them.

The DJ's energy is infectious and for some people; just seeing you enjoy yourself will make them want to have a good time.

Conclusion

Making people feel good and getting them dance is what makes you successful as a DJ. Nothing else is more important.

Preparing and knowing your music well and being ready to play outside of your comfort zone is great preparation for being able to react and adapt to a crowd.

If you've got your music organised and you know it well, then you should be able to relax, enjoy your mix, try out different tunes and make the girls dance. If you find out things don't go as well as expected, the job is to get into the minds of your crowd and you'll be able to get them warmed up and dancing in no time, whoever they are.

Credit:- http://www.digitaldjtips.com

Beginners' Guide To Keylocking

|

| The yellow musical note in Traktor Pro 2 that tells you your track is "keylocked" - but what are the dos and don'ts of keylocking? |

If you're one of those DJs who always looks at that little "keylock" button but feels unsure about how or when to use it, this is for you:

What is keylock?

Keylock fixes the pitch of a tune while letting you alter the tempo, stopping the tune getting deeper and deeper as you slow it down, and stopping it getting whinier and higher-pitched as you speed it up.What's the point of it?

When you beatmatch two tunes, if one of them is sped up or slowed down too much, it might sound "wrong". This returns it to its original pitch while still letting you play it faster or slower.

How does it do it?

It uses your computer as a digital sampler, processing and resampling the tune on the fly and feeding it back with its pitch returned to how it is when played at the correct speed.So I should just leave it switched on then?

Some DJs do, but the problem is that the work needed to "return" the tune to its original pitch can degrade the sound quality. It happens most when you deviate a long way from the original tempo, so keylock works best when you're mixing tunes that are close to their original tempos - say, no more than + or - 6% - and with simpler material. Use your ears to judge.

What's it got to do with "harmonic mixing"?

Harmonic mixing, aided by key-tagging software such as Mixed in Key, is when you mix together tunes that are in the same or related musical keys, for smoother, more musical sets. Every tune has a musical key, but when you alter its speed, as we've seen, the pitch and thus the key alter. So if a tune is in the key of C, and you move it up in tempo, it is no longer in C. It may be in C#, or D, or E etc - or just as kiley, between two of these keys. Thus if you were mixing it with another tunes in C, it would sound wrong. Keylock "returns" it to its usual key, making this kind of mixing easier.So should I use it?

If you're doing harmonic mixing, broadly: yes. If you're mixing music that sounds too high or low because you're deviating from its original pitch too much: try it, but keep an ear on the quality. One tip here is to use it to mix, but as soon as you've mixed the tune in, slowly return its tempo to 0% using the tempo slider, then turn keylock off - this will return the sound quality to 100% but still allow you to do the mix you wanted.Can you do harmonic mixing without keylock?

Yes, but it's much harder. Best is to use all tunes around the same BPM, but also, every time you add or subtract 6% of a tune's tempo, you move up or down one semitone (note), which also changes the key to one higher or lower. So a tune in C moved down 6% is now in B. Knowing this, even vinyl DJs can mix in key, as long as they know they keys and BPMs of all of their tunes.Credit:- http://www.digitaldjtips.com

Ways to use Loops without annoying anyone

Looping is where you select a section of your track, and tell the software to play it over and over again. It started with CDJ players, where there was a "loop in" and "loop out" pair of buttons. You had to time precisely when you hit the buttons to get the perfect loop.

Nowadays, with digital DJ software, because the software has already worked out where the beats and bars are on your tunes, you instead specify a start point, and how long you want the loop to be in beats or bars/measures, not in seconds, and the software will slice it precisely for you.

Assuming you have two properly beat analysed tunes playing, and you have "sync" turned on, this means that you can loop one of the tunes and the pair will stay perfectly locked together.

Credit:- http://www.digitaldjtips.com

Nowadays, with digital DJ software, because the software has already worked out where the beats and bars are on your tunes, you instead specify a start point, and how long you want the loop to be in beats or bars/measures, not in seconds, and the software will slice it precisely for you.

Assuming you have two properly beat analysed tunes playing, and you have "sync" turned on, this means that you can loop one of the tunes and the pair will stay perfectly locked together.

Important Uses Of Looping

1. Looping the start or the end of a track to aid with mixing

This was a major use when CDJ DJs first got their hands on looping, and it still is. If you are mixing from one record to another, you may want the nice rhythm from the previous tune to carry on up until the tune you're mixing in reaches its first break, for instance. By looping the last bar or two (or longer if the rhythmic phrase that you want to loop lasts longer), you can choose when to take that tune out of the mix, rather than letting the arbitrary length of the outro decide for you. This can work for bringing record into the mix too. If you have a tune with only a few beats and bars before the bassline or the vocal kicks in, you can loop those bars right up to the point where the "real" music starts.

|

| Looping the end of a track in Traktor Pro: It's a get-out-of-jail card, but don't overuse it. |

The tune will then faithfully repeat that non-musical intro section until you release the loop, so you can spend a nice long time bringing it into the mix before dropping it in totally and letting the musical section begin to play.

Watch out for: The danger is hitting "loop" at the end of every record because you're incompetent at mixing and want longer to try and do it, or you weren't paying attention and need to do it to give yourself time to find another tune! Do this more than once or twice in a set and you'll bore your dancefloor, because ultimately you're taking longer to play the same number of records.

Also, don't accidentally forget you've looped a tune. It's horrible to realise that you're starting to get bored, only to check your software and see you've been looping the first eight bars of the new tune for the past two minutes!

2. Keeping a musical phrase going throughout your set

Especially if your software/controller lets you use extra decks, you can take an interesting rhythm (or a short, distinctive musical sections such as a vocal or a synth line) from any track you like, and loop it forever on a spare deck, bringing it in and out of the mix in sync whenever you want to for your whole set. Collect a few interesting loops in your style and this could become your trademark. By using cue points you could have several lined up in specially prepared "sample tracks", or if you have Traktor Pro 2, use the sample decks in loop mode to achieve the same thing. This works well for non-musical patterns too, by the way - I DJ at a sundowner session in a beach bar, and I like to have the sound of waves lapping up against the shore and crickets / cicadas handy on spare slots, looping away, so periodically I can evoke the sound of the beach at sunset, even if there's no wind so the waves aren't lapping, and the cicadas haven't woken up yet!

Watch out for: Again, overuse is your enemy here. Especially if you're using well-known vocal snippets or synth drops, use them sparingly. Having a sprinkling of percussion to give your set some coherence is one things, but dropping Faithless's "Insomnia" riff 10 times an hour is another completely!

Also, check in your headphones that the phrase you're bringing in has remained in sync with the main tracks before you drop it in.

3. The classic "loop roll"

The classic "loop roll" effect is where you start a section of music looping (say, a bar), then after it's played four or eight times, halve the length, then four or eight times later, half it again, and so on, until it sounds like electrical hum or a machine gun, because you're looping a tiny section of the track. Then, at the right time, you release the loop, allowing the track to play on, hopefully inducing dancefloor mayhem. It is often used to get out of breaks in a tune, because when you release it, you drop in where the beat kicks in again.

|

| The Xone:DX with Serato ITCH has a loop roll feature allowing you to use loops while the track continues to play unaffected in the background, ready to drop in again when you're finished. |

Watch out for: You need to practise this to make sure it actually sounds good, and you also have to get your timing right for the drop out and the changes.

Also, when you release a loop, it will usually begin playing from the part of the song where you pressed "loop", which may not be where you would want, especially if you're using this technique for the common / cliched use of getting out of a break while adding a bit of excitement to the mix. Two ways round this last point. The first is a hack: You set a cue point for the first beat after the break, do your loop, then hit the cue point when you're done, so the track carries on playing from where you ideally would have wanted the loop to release it.

The second is to use any dedicated "loop roll" function that your software offers you. For instance, in Serato ITCH with a Xone:DX, there's loop roll feature whereby you loop as above, but the track carried on playing as if you weren't messing around with it in the background, unheard. The second you drop out of the looping, the track kicking in again where it wouldn't have been had you not started the loop section at all.

Don't do this too often, and don't do it for the sake of it on a break that has perfectly enough excitement as it is - it'll annoy people. There's skill involved here, too, so practise it at home, not in front of the audience.

Another thing

Looping works best when you can't tell you're listening to a loop. Watch out for musical phrases that start and get clipped off as the loop returns to the front, or instruments being slowly removed from the mix that then jump back up in volume as the section loops.

Sometimes you can get round these problems by not starting your loop bang on the beat instead starting it at the start of a musical phrase that happens to start somewhere else in the bar, but the key is to listen to the loop. If it sounds looped, it's not good.

Monday 13 February 2017

Compression in Audio Mixing

Compression is all about controlling the peaks and troughs (dynamics) that occur in your mix when, for instance, the quieter vocal moments are drowned out by the guitarist during recording and/or playback. In a nutshell, it squashes the loudest peaks and boosts the quieter troughs, meaning you can up the overall track volume to get that extra punch.

Compressors in Music

Its uses can be both "correctional" and creative - a correctional example might be for maintaining the trailing sustain of a guitar note where it might otherwise tail-off too early below other instruments in the mix (the sustained note of a guitar falls naturally in volume the longer it's held; the compressor can act to keep it prominent in the recording).

Creatively, you could use it for what's called, 'gain-pumping'. Commonly used in dance music for adding extra punch to the kick drum, the initial thud is "pronounced" by the compressor before being quickly released.

Let's have a look at the common parameter settings to play with.

Compressors in Music

The compressor belongs to the 'gain-based' family of musical effects.

Creatively, you could use it for what's called, 'gain-pumping'. Commonly used in dance music for adding extra punch to the kick drum, the initial thud is "pronounced" by the compressor before being quickly released.

Let's have a look at the common parameter settings to play with.

The parameters:

There are five basic controls that shape the way a compressor manipulates a sound input.

1. Threshold

Sets the decibel (dB) threshold to the level at which the compressor begins to work. If you set it to 10 dB for instance, any signal coming in above that will be have its ass shaped by the compressor according to the parameters below.

2. Ratio

This sets the amount of compression, in dB, applied to a signal once it violates your pre-set threshold.

A ratio of 4:1 will output 1 dB for every 4 dB of input signal that exceeds your targeted threshold

3. Attack

The time, measured in milliseconds (ms), it takes for the compressor to reach its maximum level on the sound.

A fast attack can be useful for damping percussive peaks so the overall track level can be increased. Can also add punch to a track.

4. Release

Controls how long (ms) it takes to release a signal from the compressor once it dips below your specified threshold.A long release time can be useful for adding sustain to a signal - on guitar solos for example.

5. Output

Sets the overall output level of the effect (dB). This can be useful to whack up the output level again after its been reduced from applying compression to a signal - this is otherwise commonly known as make-up gain.

Compression parameter guidelines for popular musical instruments.

Done.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)